Dyslexia, my friends, is a subject that’s been close to my heart for many years, especially as a mother raising my kids here in Chiang Mai, Thailand. You know, it’s quite surprising that dyslexia is the most common learning difficulty, affecting between 5 to 15% of all children. Yes, you heard that right, and half of all special education students in a school may be dyslexic. But here’s the kicker, it’s often hidden in plain sight, lurking beneath the surface, and it’s always on the radar of any parent worth their salt.

Why is it hidden, you ask? Well, the tricky part is that children with dyslexia are often bright sparks, and they don’t show any outward signs until they start learning to read. This can pose some real challenges for these kids because their reading difficulties are like a bolt from the blue, completely unexpected, given their obvious cognitive capabilities. Sadly, this perception often leads to them going undiagnosed, being misdiagnosed, or, even worse, being labeled as ‘lazy.’ And let’s not forget, in an international school setting, these dyslexic gems can easily slip through the cracks due to language barriers and a lack of proper assessment tools to differentiate between language issues and dyslexia.

Now, hold onto your hats because here’s the real kicker: without early identification and intervention before grade one, a dyslexic child has just a 1 in 4 chance of reading at grade level by the end of elementary school. But, and it’s a big but, that same child who gets structured, cumulative, and multisensory instruction in kindergarten or grade one? Well, they have a whopping 90 to 95% chance of reading fluently by the end of elementary school! That’s why early intervention is absolutely vital. Without it, these dyslexic little ones could end up with lifelong learning hurdles, a fear of learning, low self-esteem, and even depression.

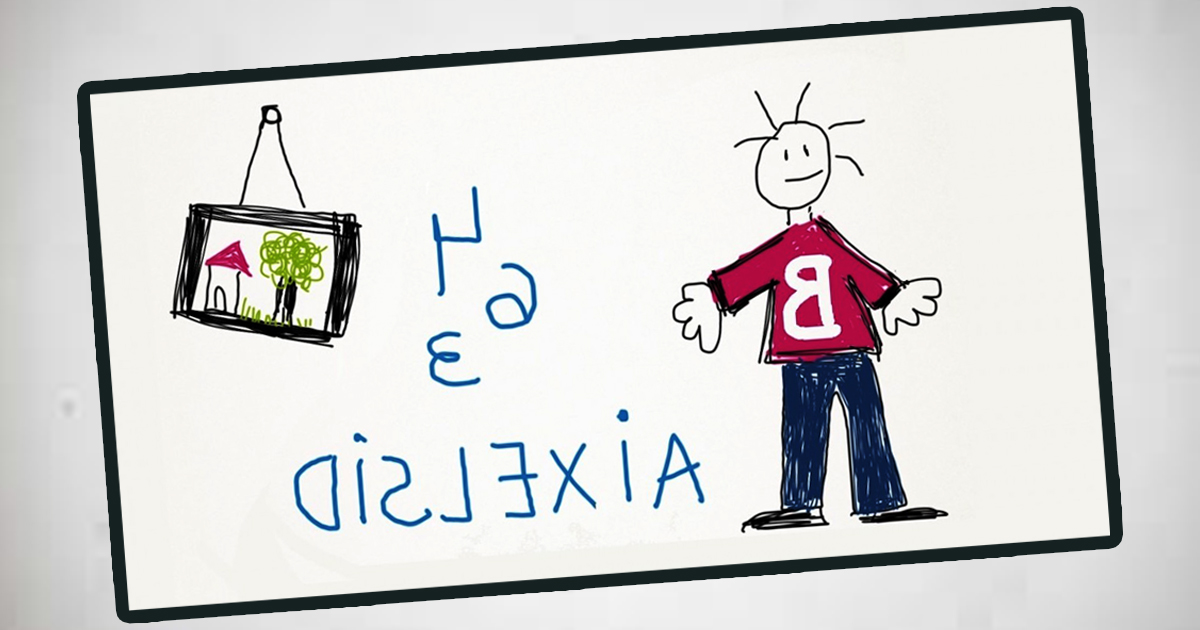

Understanding Dyslexia

You see, our brains are wired to pick up many skills naturally. Just think about how our kids learn to walk and talk without any special instruction. But here’s the thing most folks don’t realize: our brains weren’t designed to read.

Dyslexia, my dear readers, is a neurobiological difference. Recent brain imaging research has shown that dyslexic children don’t use the same brain areas when they read as their non-dyslexic counterparts. And the areas they do use are inefficient when it comes to processing language elements. It’s like the wiring to the language parts of the brain is unplugged. Recent Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies have given us a window into why dyslexic kids struggle to read. But, and this is the good part, research has also shed light on the types of instruction that can make those brain pathways hum with activity again. Structured, cumulative, and multisensory programs, like the Orton-Gillingham language program, have shown they can rewire those neural pathways, making the reading areas in the brain more efficient.

If you’re interested in multisensory language programs for dyslexics, you can find more information at www.dyslexiaida.org. And here’s a tidbit for you: Stanislas Dehaene, a bigwig in reading and math brain research, points out that reading forces us to repurpose parts of our brain that were originally designed for other tasks. Luckily, the language and visual object recognition networks in the brain mature in early preschool years, adapting to tackle reading.

Now, reading in a language like English demands that we blend speech sounds (phonemes) with letters (graphemes). This skill needs us to quickly and accurately perceive both speech sounds and letters. The visual word form area in the brain, tucked away in the left hemisphere at the base of the occipital lobe, handles this. It’s pretty darn fancy, actually. It lights up when we’re asked to determine if words like “READ” and “read” are the same words. Despite their different shapes, uppercase and lowercase letters like “A” and “a” or “R” and “r” have to be seen as the same. And that’s not as easy as it sounds.

For many with dyslexia, this part of the brain doesn’t quite play by the rules and doesn’t specialize in written words. Recent research even suggests that dyslexics struggle with hearing the sounds within words and recognizing letters. In simple terms, kids who find reading tough have issues hearing the sounds in words and recognizing letters. Not a great combo for reading.

New Research Areas

Here’s where the exciting part comes in: recent discoveries in brain science aren’t just helping us understand these brain regions better; they’re also showing how targeted interventions, like Fast ForWord, can improve reading skills and activate those crucial brain areas needed for successful reading.

With so much on the line for unidentified dyslexic children, knowing the early warning signs of dyslexia and the best teaching methods is crucial for their future success, both academically and in life. Dyslexia doesn’t have to hold a child back; with the right tools, they can thrive in the mainstream education system.

If you’re interested in more research about Fast ForWord and dyslexia, you can read all about it here.